Soil resistivity is the foundation of every grounding and earthing design. Determination of how easily the fault current dissipates into the earth, depends directly on the soil resistivity. It influences the size of the earthing grid, step and touch potentials and overall safety of the project. A well designed grounding system fails, if the soil model selected is wrong or incorrect soil resistivity assumption is chosen.

Table of Contents

What is soil resistivity?

Soil resistivity is the resistance offered by earth to the flow of electric current. It varies depending upon the moisture content, temperature, soil composition, porosity, and dissolved salts. Low resistivity soil conducts the fault current more efficiently which allows smaller and economical earth grids, while high resistive soil like rock and dry sand performs poor electrical conduction therefore requiring larger, deeper or enhanced grounding systems.

Why soil resistivity is critical for substations?

Soil resistivity determines the effectiveness of the substation grounding system. It has a direct control over the achievable grid resistance and it influences the touch and step voltage of the system. High soil resistivity makes the conductor spacing of the grounding grid denser (Closer), which requires more number of vertical electrodes, chemical electrodes and deeper grid placement for safe disposition of fault current with more ground ring electrodes and counterpoise electrode as well. Since higher resistivity of the soil requires more copper or steel, it has a impact on the overall grounding design and project CAPEX.

Factors affecting the soil resistivity

The factors which affect the resistivity of the soil are listed below:

Moisture content of the soil: More the moisture content in the soil, better is the ionic movement. This movement of ions, greatly reduces the soil resistivity. It shall be noted that even small increase in the moisture content dramatically enhances the moisture conductivity. [source: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/15/8/302]

Temperature: Cold or frozen soil loses conductivity because of restrictions of ionic mobility which causes the resistivity of the soil to rise steeply around -1 to -3-degree Celsius with 0-degree Celsius effective threshold. Warm and moist soil provides better conductivity.

| Temperature | State of moisture | Soil Resistivity change |

| + 20°C | Liquid | Low resistivity |

| 0 °C | Moisture starts freezing | Resistivity increases 5 -10x |

| -5 °C | Mostly frozen | Resistivity increases 20-100x |

Based on multiple studies of IEEE and soil physics.

Composition of soil: Composition of the soil also impacts it’s resistivity as clay rich soil can conduct electricity because of it’s high moisture retention capability, while sandy and rocky soil exhibits high resistivity.

| Types of soil | Resistivity |

| Clay | 20-100 Ω·m |

| Sandy | 200-2000 Ω·m |

| Rocky | 1000 Ω·m and above |

Salt or ion content: Higher the dissolved salt concentration, better is the ionic conductivity of the soil. This reduces the resistivity of the soil substantially, improving the fault current dissipation.

Compaction: Compaction makes the soil resistivity go lower by removing the air trapped in various pockets during backfilling or in loose soil. As air is a near perfect insulator with resistivity of 10¹⁴ Ω·m approximately, presence of air pockets reduces the pore water continuity, breaking the ionic conduction path. Hence, it is removed by manual or mechanical compaction.

| Type | Resistivity |

| Loose backfill | 2-5 times the native soil. |

| Disturbed soil | 1.5-3 times the native soil |

| Well compacted | Close to native soil, sometimes 20-40% lower. |

Interpreting the soil resistivity results

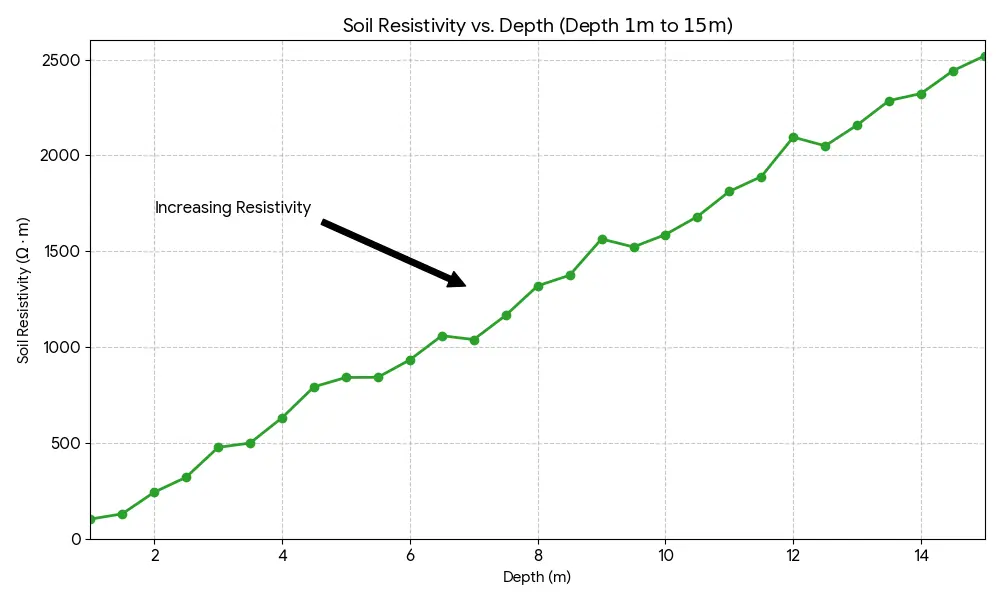

The results are often plotted in a graph, where x axis represents the depth in meters and y axis represents resistivity in ohm-meter. If the graph rises gradually, it means each deeper layer has a higher resistivity. Like Top soil> Dry sand> Rock. Here, horizontal grounding is suitable.

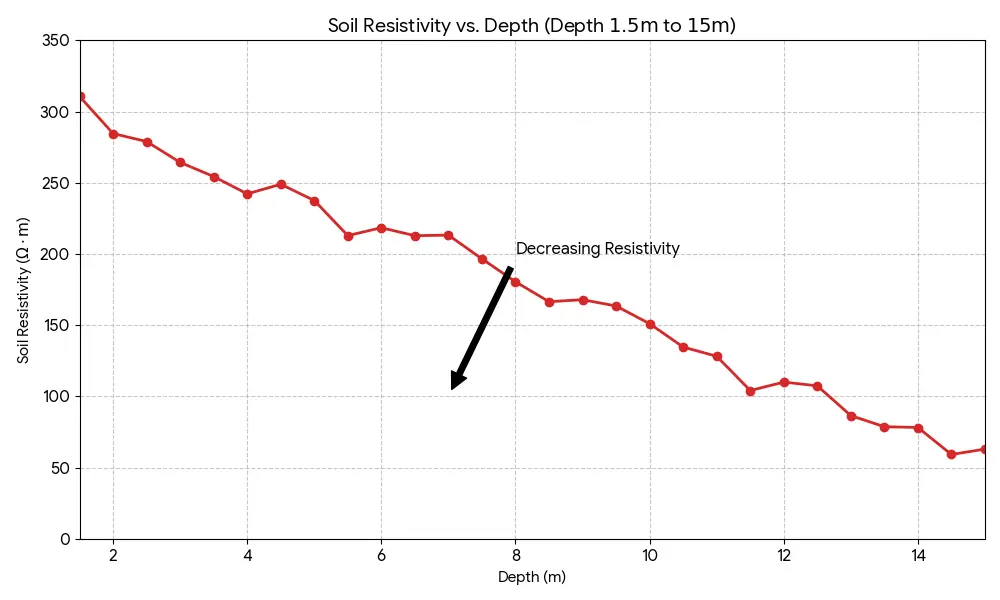

If the curve gradually falls, it means that the deeper layers are more conductive, which is common in areas with dry top soil and moist clay below. This condition is more suitable for vertical grounding electrodes.

When the soil layers are not uniform the graph shows sharp spikes and sudden drops like a flat-spike-flat pattern. This requires use of average value of resistivity or a multilayer analysis using software like CDEGS or ETAP.

Practical tips

- When the top soil is highly resistive, shifting the grounding grid to a depth of 0.8 to 1 m helps reach the moist and conductive soil, reducing the grounding resistance.

- For extremely high soil resistivity, use of bentonite, chemical electrode or earthing layer helps achieve acceptable grounding resistance by lowering the local soil resistivity.

- Measurements must be taken after site clearing, which essentially means clearing roots of vegetation, removing buried metals, pipes, which provides false reading because of parallel conductive paths.

- Never rely on values from adjacent substation as value varies drastically.

- It is better to take the value in the dry months as in monsoon affected region, the resistivity value changes sharply.

This article is a part of the Safety and Earthing page, where other articles related to topic are discussed in details.