Fall of potential test is a field method used to determine the earth resistance of the grounding system of substations, power plants, and transmission line structures. The fall of potential test is based on the principle of measuring the voltage drop in soil caused by injecting known test current into earth via earth electrodes placed at defined distance. Then by analysis of the variation in measured potential with respect to electrode spacing, the true resistance of the grounding electrode under test is accurately determined.

The fall of potential test is especially important for large or complex earthing system where single clamp or stake method results in inaccurate measurement because extensive grounding networks often have multiple parallel earth paths. Clamp on testers measures the loop impedance and often gives artificially low value reading because of the existing parallel earth paths, which does not represent the performance of the earth electrode system during fault. Also, soil non uniformity in large grounding networks affects the measurements of simple stake method as this method assumes uniform soil and radial current flow.

Table of Contents

Principle of operation of fall of potential test

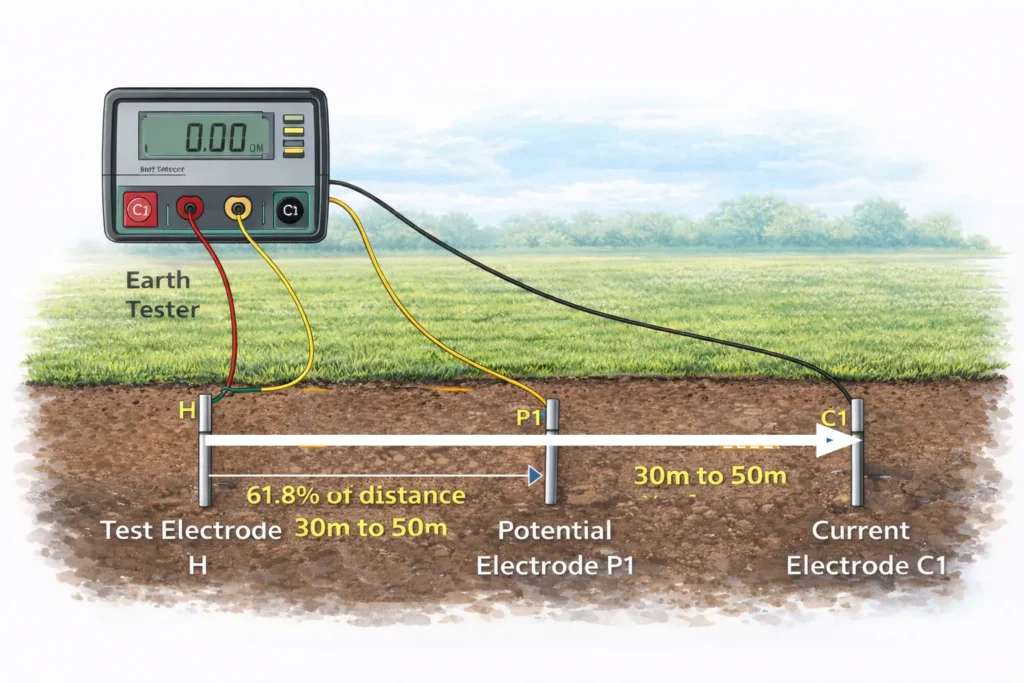

The fall of potential test operates on the fundamental principle of Ohm’s law. With this test the earth resistance is determined by measuring the voltage drop produced by a known value of current flowing through the soil. In fall of potential test, the test current is injected in to the ground through a remote current electrode which is placed at a sufficient distance typically 30 to 50 meters to avoid mutual interference with the earth electrode under test.

A second auxiliary electrode, known as the potential electrode is positioned between the test electrode and the current electrode. As the test instrument drives the test current into the soil, it measures the voltage between test electrode and potential electrode. The apparent earth resistance is then calculated as a ratio of the measured voltage to injected current.

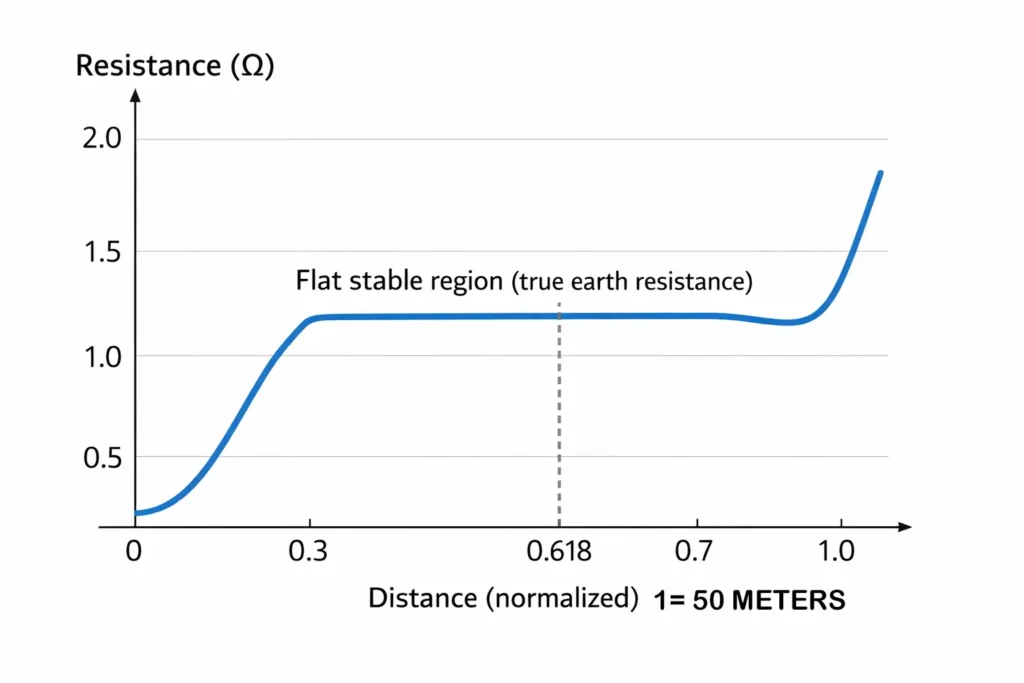

To obtain the true earth resistance value, the potential electrode is moved incrementally along a straight line and the resistance readings are then recorded at each position. The measured resistance value stabilizes when the potential electrode is moved at around 61.8% of the distance between the test and current electrodes (61.8% away from the test electrode) indicating no resistance zone overlap. The stable resistance value represents the actual earth resistance of the test electrode.

Test Equipment required

The fall of potential test requires a dedicated earth resistance tester capable of injecting a controlled AC test current and measuring the resulting voltage drop. Two auxiliary electrodes are required, a current electrode and a potential electrode, typically made of steel or copper rods. Insulated test leads of adequate length is required for the connection of the equipment to the auxiliary electrodes and the test electrode. A measuring tape or distance wheel is needed for positioning the electrodes accurately along a straight line as per the desired length. A hammer or driving tool is required for installing the electrode in the soil.

Test setup and electrode placement for Fall of potential test

In the fall of potential test, the earth electrode under test is first isolated from all parallel grounding paths. The current electrode is driven into the soil at a significantly large distance typically 30-50 meters away from the test electrode along a straight line. The potential electrode is placed in between test and current electrode. All three electrodes are aligned to minimize the measurement error. The earth resistance tester is then connected accordingly with the insulated lead.

Step1: Obtain the work permit and ensure that the system is fully deenergized and isolated.

Step 2: Disconnect the grounding lead of the electrode under test.

Step 3: Drive the current electrode C1 into the soil along a straight line at a distance of 30-50 meter from the test electrode to avoid the overlapping of resistance areas.

Step 4: Place the potential electrode P between the current electrode and the test electrode and connect all insulated lead to the earth tester.

Step 5: Inject the test current and record the resistance reading while shifting the potential electrode in equal steps.

Step 6: Plot the resistance values in a resistance vs distance graph and identify the stable region. For simpler installations single value at 61.8 % of the length between the test and current electrode is sufficient as it always falls on the flat or stable region in the resistance v/s distance curve.

Step 7: The stable resistance value is taken as the actual earth resistance of the test electrode.

Step 8: After the test, reconnect the grounding lead and restore the system back to original state.

In fall of potential test, the injected test current is usually very small and non-hazardous. It typically ranges from 1mA to 50 mA AC, depending on soil resistivity and electrode spacing. The test frequency is usually greater than 100 Hz to avoid interference from power frequency currents. The exact current is automatically selected by the earth resistance tester to produce a measurable voltage drop. The current is not sufficient to simulate a fault condition but is only for the measurement. AC current is used to eliminate the polarization effect in soil. Higher current can be injected in high resistivity soil but is still within milliampere level.

Acceptance criteria for Fall of potential test

Acceptance limit for substation earthing is governed by safety requirements rather than a single universal value. In practice, most transmission and distribution substations are designed to achieve overall earth resistance of 1.0 Ω or less. For EHV substations, with extensive grounding grids, values in the range of 0.1-0.5 Ω is commonly targeted while smaller distribution substations can permit slightly higher values. The earth resistance of transmission tower footing is usually below 10 Ω.

Measured earth resistance obtained from fall of potential test should be compared with the original design value, specified in the grounding study. Acceptance is confirmed when the measured resistance is equal or lower than the design value.

Common Errors and precautions

Influence of nearby earthing system

Adjacent grounding systems, buried metallic structures, pipelines or cable sheaths can overlap resistance areas and distort the test results. This often leads to artificial low resistance values. Therefore, adequate spacing of auxiliary electrodes and selecting test direction away from parallel earths are essential to minimize interference.

Soil moisture and seasonal variation

Soil resistivity varies significantly with moisture content and temperature. Tests conducted during dry season may yield higher resistance values compared to monsoon conditions. For meaningful assessment, results must be compared to historical data and design assumptions based on worst case or dry soil condition.

Lead resistance

Long test leads, damaged insulation, or loose connections introduce additional resistance and unstable readings. Poor contact between the probes and soil further increases the measurement error. Therefore, clean connections, firm electrode installation and verification of lead continuity are essential for accurate and repeatable results.

This article is a part of the Testing and commissioning page, where other articles related to topic are discussed in details.